Why can’t the UK face up to its crisis

Interview with Rafael Behr on the long-term price of the Brexit fraud

It is perfectly possible that economics departments in universities around the world will soon be running courses entitled “Bust Britain,” or “How to Explain the UK’s Collapse,” or “The Decline and Fall of British capitalism”.

We will become a curiosity and a cautionary tale. We will be seen as the new Argentina or Italy – another country that was once prosperous and still ought to be prosperous, but has veered off the road for reasons that baffle even the finest minds.

The economic historian Brad DeLong asked last week

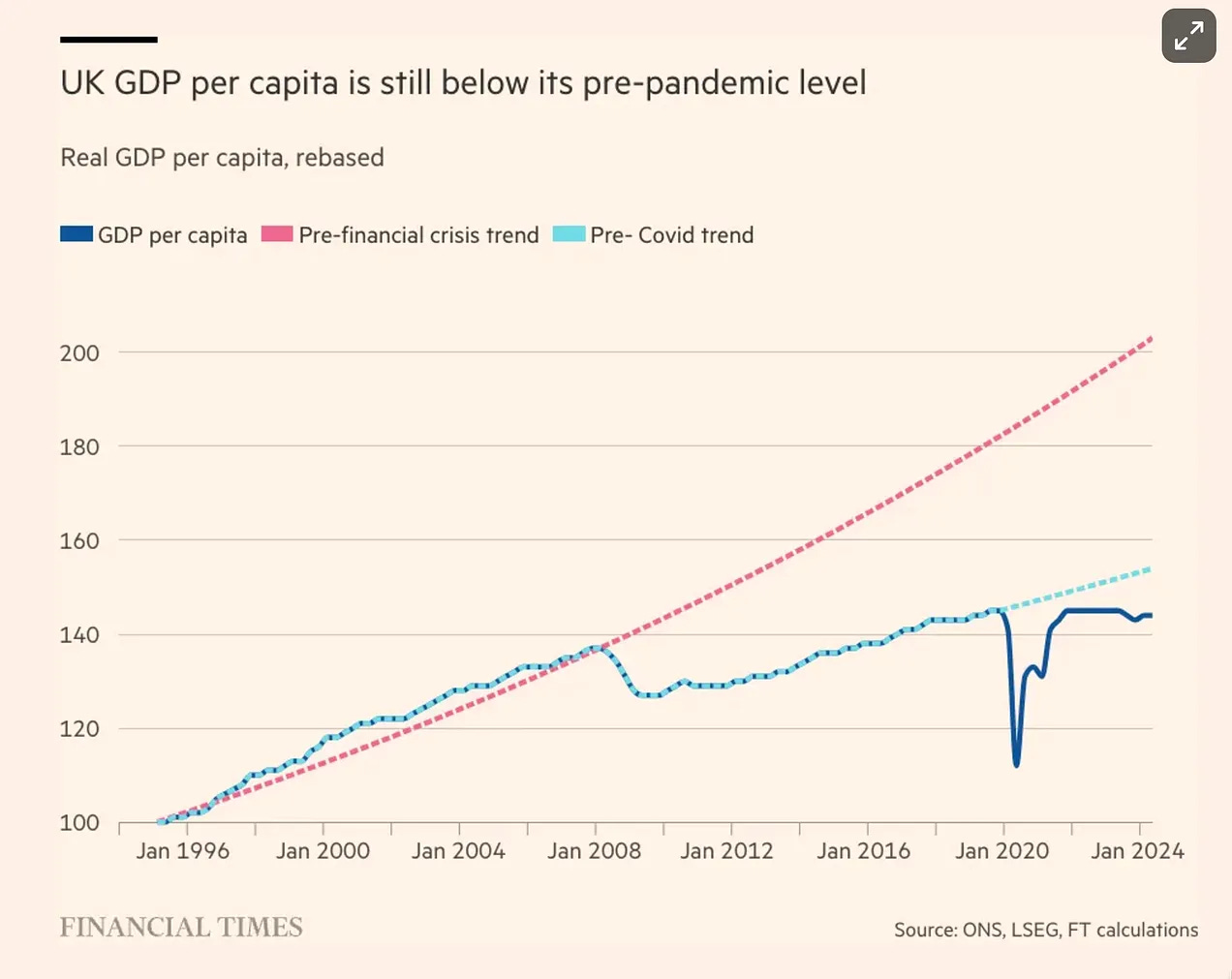

“What happens when a global financial hub bets on the wrong policies at the wrong time? Britain's story since 2008 is one of lost potential, economic stagnation, and grave self-inflicted wounds. And even those are not enough to account for it, even as we pile policy missteps on top of structural failures.”

And then with a statistic which ought to be burnt onto the national consciousness, he continues: “Had Britain maintained its pre-2008 growth trajectory, it would be 40% richer today.”

The financial crisis, austerity, Brexit and Covid were temporary failures but they have had permanent effects for reasons no one can quite explain.

The sum of the damage outweighs the parts. No wonder we are an object of horrified pity.

Meanwhile, we have grown used to decline. Like a debilitating illness, it has become a fixture of modern life that has been around for so long we barely even notice its existence. Living here, reading the papers, watching the BBC, and listening to our politicians, is to be in a country that would rather die slowly than contemplate serious reform.

Change for the better is so hard to imagine, it is barely even discussed.

It seems somehow fitting that the most significant measure from our new Parliament is to allow the state to assist in the death of the terminally ill with, one assumes, lethal injections or overdoses. Suicide fits the national mood.

In the latest edition of the Lowdown, I talk to the Guardian political columnist Rafael Behr about the pervasive and enervating gloom.

You can listen to it here on Apple

Here on Spotify

I asked why we cannot face our problems. Behr’s answer was that the “fraudulent revolution” of Brexit has exhausted the country.

There is no appetite for “telling the public; Look, something has gone terribly, terribly wrong and we're going to have to think big and take drastic action to fix it. The political culture just can't accept that now.”

Our radical change came in 2016 with the Brexit referendum. All the effort and division that followed merely led to stagnation and decay, and to a weary determination not to reignite all that tension again.

Never forget that Labour won with a manifesto that offered only minor change. It promised NOT to seek to rejoin the EU or even the Single Market, and NOT to raise income tax, VAT or national insurance.

Given the state of the country, it is absurd to be complacent. But psychologically it makes a cowardly kind of sense. Brexit, and in Scotland, the independence argument, have exhausted us.

As Rafael puts it:

“All of the emotional and political capital that you can spend…in pursuit of a broader national goal was squandered on Brexit. And you don't get another shot at that, in the same generation.”

In other words, Brexit was a gigantic waste of everyone’s time. You can see that today when not even its supporters dare not talk about it, let alone celebrate it. What Conservatives thought would be a national liberation has become a national embarrassment.

Behr said:

“I'm very confident, and I remember writing this at the time, that there will never be a day when Nigel Farage is on UK Bank Notes and the 23rd of June [the date of the Brexit referendum] is a national holiday. There will be no monuments to Jacob Rees Mogg and Boris Johnson.

“The opportunity for the firm smack of ideological clarity, which is something that I think Keir Starmer ought to have been able to deliver after July when he won a massive majority, was not there.

“That could have been a 1979 moment for the centre-left and it isn't and I think one of the reasons it isn't is that sense that our civic fibres have been torn and atrophied and demoralized.”

The character of Keir Starmer matters, too. He isn’t an evangelist or a showman, but a quiet and dedicated public servant: maybe too quiet and too dedicated for our dishonest times.

Behr again:

“He is in his 60s, he comes from a working-class background. He's quite emotionally uptight. He's tight lipped. He doesn't show emotions. He doesn't wear his heart on his sleeves.

“He’s the opposite of Boris Johnson in so many ways. And you can tell he genuinely despised Johnson. Starmer believes you shouldn't be boastful. You should do your talking on the pitch.”

All of which I like, but I am hardly typical. Starmer cuts an awkward figure in our culture which encourages demagoguery and hysteria. It is an open question how well he and the Labour party will fare in the second half of the 2020s.

As Behr says, along with Starmer’s rather old-fashioned manner is a dangerous naivety about the British state. If you want to restore stability after the chaos of the Tory years, you can easily fall into an overly nostalgic belief in its wisdom and effectiveness.

Labour defended civil servants and judges as the Tories claimed they were woke elitists or liberal saboteurs. It failed to notice that the constant attacks and spending cuts had pushed many talented civil servants away. Labour ought to make reforming the public sector its first priority and ensure that the systems are in place to deliver its programme.

But, as Behr says, “reforming the state and changing the way everything is done is boring, wonkish, under the bonnet delivery stuff that no one really understands.”

If you do it, you take up a lot of time and energy. But if you don’t do it, you won’t deliver to the voters.

To sum up, we have a government with a massive majority that was elected on a massively modest manifesto. It promised to leave the status quo largely intact, even though the status quo is failing and Britain is a country experiencing extraordinary decline. The prime minister is an old-fashioned man, who is relying on a hollowed-out state, that may not even work effectively, as he seeks to return to order and stability after the UK’s populist riot.

All that would be bad enough, but we cannot stop there.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Writing from London to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.