What our politicians can’t say and our media won’t report

The inability to confront the UK’s decline

If you sign up as a subscriber not only do you get access to all posts, archives and podcasts, BUT you also allow me to carry on writing. A subscription costs £1.15 a week, and there is a free trial on offer too

We would be in a great deal less peril if Keir Starmer, our next prime minister, could be honest. When journalists ask him to rule out raising taxes, for example, or returning to the EU, or whatever else their editors want to hear him prohibit, Starmer ought to be free to reply, “Obviously I do not want to cause unnecessary turmoil. But we are facing a crisis, and it would be the height of irresponsibility for me or any other leader to reject unilaterally policies we might need in an emergency.”

Starmer cannot say anything sensible because the headline in the papers or on the BBC would not be “Labour wants to keep the UK’s options open,” but “Labour wants to raise taxes.”

As our problems grow deeper our debate becomes shallower. Politics has become a game in which received opinion takes pieces off the board until no move is possible except staying within the status quo. Unfortunately for the UK, that status quo is no longer sustainable.

Two think tanks, UK in a Changing Europe and Full Fact, have just released The Policy Landscape 2023. In it, they collect the best public policy thinkers and ask them to draw up the UK’s “to-do list”. It exposes the gap between the reality of the UK’s emergency and our petty and performative “debates” better than anything I have read this year. Let me go through a couple of the arguments.

Public finances

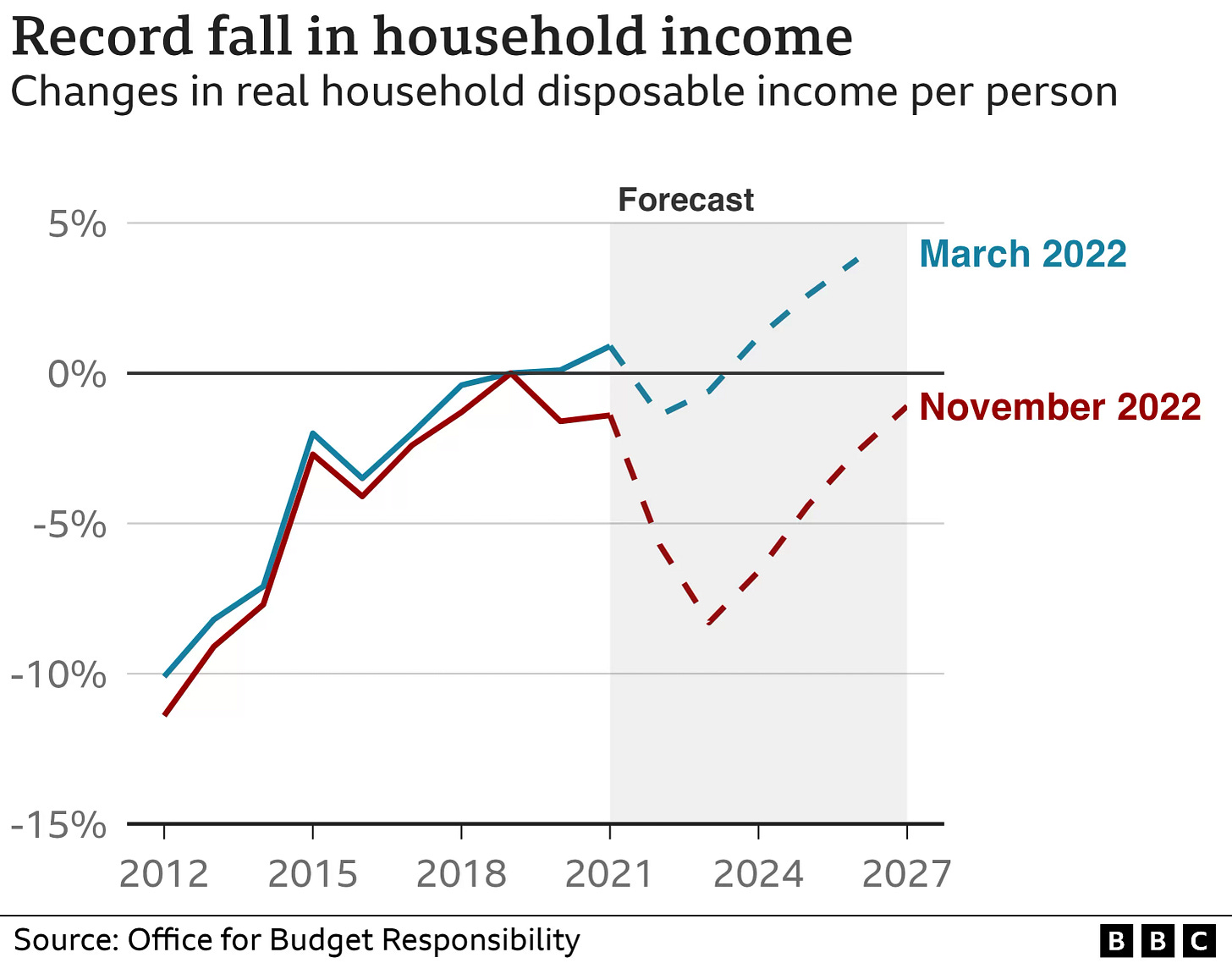

You probably know the markers of our national decline. Household living standards are in the middle of the largest two-year fall since records began in the 1950s. The drop comes after the longest period of stagnation since the Industrial Revolution, and the elevation of interest rates and inflation to their highest levels in a generation. Public debate is largely confined to discussion of mortgage rates. Journalists have mortgages, or at least their editors do (junior reporters cannot afford to take one on) and their cost is a matter of personal concern to them and to their wealthier readers.

As Ben Zaranko of the Institute for Fiscal Studies argues much more should be written about UK’s debt servicing costs. They will batter the UK’s public finances for the rest of the 2020s. All Western countries must cope with the interest rate shock, of course. But the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) points out that the UK is particularly vulnerable to interest rate rises as it has excessive amount of debt tied to the Bank of England rate.

Despite taxes rising to their highest levels since the 1940s, and despite the budgets for public services – many of which are still in a parlous state post-pandemic – being fixed in cash terms and therefore squeezed by higher-than-expected inflation, the government can still barely stick to its fiscal targets.

Meanwhile the Conservatives have put out public spending estimates for 2025 and beyond that are a crass political trap for an incoming Labour government rather than reachable targets.

Novel problems are not being met. As the Institute for Fiscal Studies says, the shift to electric cars will mean the loss of tens of billions of pounds of revenue from fuel duties. But the Conservatives have not come up with a “hint of a plan to address this with road pricing or anything else”. Nor to be fair has any other party. In a culture where modest measures against car exhaust emissions produce nervous breakdowns, road pricing is impossible to discuss, even though we must discuss it. Indeed “we can’t talk about what must be said” could be this country’s slogan.

Meanwhile the number of people aged 85 and over is projected to increase by 19% between now and 2030, and 57% by 2040. And yet since 2010 we have tried and failed to introduce a workable and equitable system of care for the elderly. Now we seem to have given up. It is a fair bet that the subject will be absent, along with every other hard choice, from the next election campaign

Or as the The Policy Landscape report puts it

“Neither party seems willing to confront the public with the reality that even maintaining the quality of our public services, let alone substantially improving them, almost certainly means higher rather than lower taxes. Talk of pre-election tax cuts feels increasingly detached from that fiscal reality.”

Of course there would be no need to raise taxes and cut spending if we could get the economy to grow.

Alas, we cannot do that either

Growth

GDP per capita is less than 4 percent above the level in 2008, compared to an increase of 40 percent in the previous 15 years. We have been stagnating for the better part of a generation, and you might think that plans to end the lost years would be a matter of political urgency.

Not so. Labour is being braver than its left-wing critics like to admit by promising to remove at least some planning constraints on home building and development. I can see the Tories making Labour suffer for it in rural seats at the next election. I hope Starmer has the courage to stick to his planning reforms for all the electoral damage it might cause, because as far as I can see it is the only significant pro-growth policy either of the major parties possesses.

In private, every sane politician knows that an easy gain for the economy would follow the UK beginning immediate talks with the EU on rejoining the single market. It’s not about to happen. I will be releasing a podcast later this week on why it is politically impossible for opposition parties to turn the Brexit disaster to their advantage. But whatever the reasons, they cannot point to the calamitous economic error of Brexit, and promise to rectify it. And because they will not fight Brexit, we cannot increase growth by returning to free trade with our neighbours inside the EU once the Tories have gone.

Jonathan Portes of Kings College, London, offers depressing reading to anyone who looks to other sources of economic revival.

Training? We’ve hacked back the further education budget for years now. Industrial policy? Nice idea if our politicians could stick to one. Taxation? Portes points out that we are not overtaxed by European standards. But he adds that we are very badly taxed. Unfortunately, reforming the tax system appears to be as politically impossible as having a grown-up conversation about Europe.

All the authors in the report agree that the UK’s crises are interlinked

“The impact of the cost-of-living crisis,” writes Mike Brewer of the Resolution Foundation, “has been exacerbated by the UK’s low growth and high inequality which has left too many households with too little financial resilience. Low productivity has real consequences: real wages grew by 33% a decade from 1970 to 2007, but this fell to below zero in the 2010s. If wages had continued to grow as they were before the financial crash of 2008, real average weekly earnings would be around £11,000 per year higher than they currently are. And against this backdrop of low pay, the UK had greater income inequality than any other large European country, exacerbated by large cuts to working-age benefits, especially to low-income families with children. As of 2019, the lowest-income families were already spending 60% of their income on essentials, meaning there was no fat to trim. The period of rapidly-rising prices may be over, but if we are ever to have shared prosperity, the UK will need both higher growth and lower inequality.”

On the state of the public services, I was struck by how easy it was for our political culture to ignore their long decline. When there’s a crisis, like school buildings threatening to collapse on pupils, we take notice. But the weary debilitation of the last decade has been easy to ignore. Carole Willis of the National Foundation for Educational Research writes about how the number of trainee teachers has failed to meet the government’s targets not just for one or two years, but year in and year out for more than decade, as schools gradually and, as far as the media culture was concerned, imperceptibly sank down.

You can paint the same picture in every public institution, even in sectors such as defence and law order, which the Tories once looked after, but are now as dilapidated as every other service.

Sam Bowman recently wrote a widely acclaimed post which argued that Britain was now a developing country. It should be seeking catch-up growth with the advanced economies of the world rather than complacently thinking of itself as a rich society. A reasonable catch-up programme would take as its first principle: whatever the Tories did, do the exact opposite. We would

Rejoin the EU

Shift tax from income to wealth

Allow new home, office, laboratory, and factory building.

Prioritize the young rather than the old.

You only need to write these sentences to realise how politically impossible change has become. And yet you need only look around to realise how economically unsustainable the status quo has become. Something must give. And if it doesn’t, we will be in a full-scale crisis come the second half of the decade.

Without subscriptions, so if you like my writing please consider signing up or taking out a free trial. There are all kinds of benefits AND you allow me to carry on working.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Writing from London to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.