Rory Stewart and the death of moderate conservatism

It couldn’t cope with the modern right – or even understand it

Conservative leadership candidates (R-L) Boris Johnson, Jeremy Hunt, Michael Gove, Sajid Javid and Rory Stewart at Conservative party leadership debate 18 June 2019. [Handout photo/EPA/EFE]

The weekend political column is free to read. But please sign up as a free subscriber to receive more posts. Or you can help me carry on writing by becoming a paying subscriber. You will then receive access to all posts, archives and podcasts for £1.15 a week, and there is a free trial on offer too!

If, and it is a big if, the next Labour government changes the United Kingdom for the better, it will be because politicians entirely unlike Rory Stewart drive it on.

They will not have been to Eton. They will not have governed a province of Iraq. They will not have run charismatic leadership campaigns and starred in acclaimed podcasts. They will accept the party line, trudge through the division lobbies, and agree that significant reform requires discipline and the abnegation of the self.

“Politics is a strong and slow boring of hard boards,” said Max Weber. “It takes both passion and perspective.” If we are lucky, Labour will give us slow and boring politicians determined to enact a programme of national renewal. The portents look good. On both the slowness and the dullness Sir Keir Starmer is already leading by example.

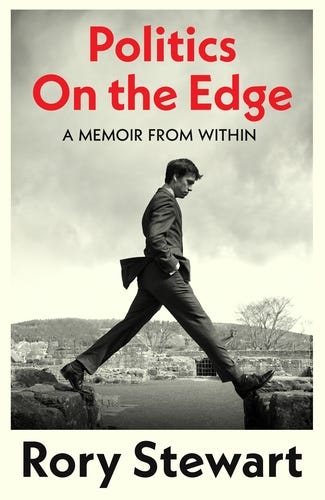

Like its author, Rory Stewart’s memoir Politics on the Edge (out this week from Jonathan Cape) is neither slow nor boring. It is one of the most brilliantly stupid books I have read. Brilliant because it is an angry yet scrupulous dissection of the corruption of the Conservative governments he served. Stupid because Stewart fails to understand the populist forces that destroyed his moderate version of conservatism and his own career.

Stewart is a man of the 1990s. Readers old enough to remember that time will recall how Jeremy Paxman and Have I got News For You mocked spin doctors and the professional politicians they served, and how every half-educated journalist (your correspondent included) imitated their tone of ineffable superiority.

They will recall critics saying that robots staffed the Clinton and Blair governments. They were dumb. They were self-obsessed. They were greedy. They were only in it for themselves. In those innocent days we thought spin doctors were the worst the world could throw at us.

The wave of anger that destroyed the old regime of the West had many causes, most notably the financial crisis of 2007/08. But the anti-political style of dismissing all politicians as corrupt and mendacious, cleared the way for authoritarian rule too. In the US, Brazil, Hungary, and the Philippines, it led to “the people” or a large chunk of them, despairing of representative democracy, and turning to fraudulent strongmen who promised to “drain the swamp” and “end business as usual”. In the case of the UK, it ended in the public or a large portion of it supporting Boris Johnson – himself a Have I Got News for You stalwart – Jeremy Corbyn, Alex Salmond or any other leader who promised to smash the rigged system and replace it with… well they were never quite sure with what

Stewart stays true to his 1990s roots. In Politics on the Edge, he describes the idiocies of the old ways of governing with an insider’s knowledge. Like many civil servants and moderate Tories I have interviewed, Stewart despises David Cameron more than Johnson or Liz Truss. It’s not that they think he was as disastrous. Rather it is as if they see Cameron as the UK’s Louis XVI or Tsar Nicholas II: a fool who failed to understand the dangerous forces he was playing with.

In Stewart’s case there is also the traditional loathing of one Etonian for another, even more acute when the other Etonian is so notably more successful. Stewart was serving in Afghanistan in 2006 when Cameron, already the leader of the opposition, flew in. Stewart records that all the future prime minister could manage were platitudes about supporting British troops for doing “difficult and important work.”

When Stewart tried to tell Cameron that sound bites would not cut it, and the position on the ground was more complicated and dangerous than he understood. “Two small red dots appeared on his cheeks. Then his face returned to a smile.”

Stewart is engagingly frank. He pretty much admits that, when he won a seat in the House of Commons in 2010, he expected that his reputation as a modern Lawrence of Arabia would persuade Cameron to make him a minister, and was angry when he was left on the backbenches.

He rapidly came to dislike the House of Commons. MPs voted for bills they disagreed with or knew nothing about, he complains. Their debates were fatuous. “Too few of our conversations were about policy, too much of our time was already absorbed in gossip about the promotion of one colleague, or the scandal engulfing another. Even four weeks in, I sensed more impotence, suspicion, envy, resentment, claustrophobia, and Schadenfreude than I had seen in any other profession.”

Stewart watched Cameron promote unworthy Tory colleagues for all the wrong reasons. The prime minister did not care about their ability or principles. All that mattered was their loyalty to their master.

“I divide the world,” Cameron liked to say, “between team players and wankers: don’t be a wanker.” A team player, Stewart explains, was someone who parroted the party line “with fervour, never rebelled, and was never abashed. His younger promotions – Priti Patel, Liz Truss, and Matt Hancock – took this to a vertigo-inducing extreme."

You can hardly say that talent was the first concern of a prime minister who rewarded that gruesome crew and Stewart is justifiably scathing.

When he finally became a junior minister, Stewart worked for Truss in the environment department. Stewart is a fine writer, and he presents a terrifying picture of Truss: smiling, shiny-cheeked, wide-eyed, and utterly convinced of the righteousness of her prejudices. He also worked with Boris Johnson at the Foreign Office and wrote a deservedly famous account of Johnson’s laziness and mendacity for the Times Literary Supplement.

In this memoir he goes further and describes how Johnsonian deceit engulfed the entire party after Brexit.

When Stewart stood to be leader of the Conservative party in 2019, all the other candidates “argued that the UK could leave all customs and regulations alignment with the EU, without having to erect any border in or around Ireland, while preserving the full benefits of access to the European markets. And that they could achieve this by 31 October or, at worst, by the end of the year. Furthermore, none of them was prepared to say that Boris Johnson was manifestly unsuitable to be prime minister. It was this that shocked me most profoundly.

“I had found, working for Liz Truss, a culture that prized campaigning over careful governing, opinion polls over detailed policy debates, announcements over implementation. I felt that we had collectively failed to respond adequately to every major challenge of the past fifteen years: the financial crisis, the collapse of the liberal ‘global order’, public despair, and the polarisation of Brexit. None of this was helped by the British media – which was either unblinkingly hostile, like the Guardian and the Mirror, or absurdly credulous and enthusiastic like almost all the remaining press."

I don’t know about you but I can take any amount of this stuff. Castigations of Johnsons and Truss, and then of the whole Conservative party stroke and flatter my prejudices. But then if I were on the nationalist right, an after-dinner speech by Boris Johnson would have the same effect. Ditto with a Jeremy Corbyn rally if I were on the far left. Just because I enjoy it doesn’t make it true.

Stewart cannot tell the whole story because he does not understand the failings of moderate conservatism. The most glaring is its self-delusion. There was no way the party would accept him or any other liberal conservative as its leader. The Tories are a hard right-wing party now and becoming more right wing with every passing year.

More particularly, Stewart fails to understand that the politicians who did the most damage in the last two decades were not the party liners he denounces with such contempt in this memoir. More important than the MPs who did as the whips told them were Nigel Farage and obscure Conservative backbenchers who kept the anti-European cause alive decade after decade.

No one could accuse them of being in thrall to focus groups and spin doctors. They were principled men and women, whose principles led their country to disaster.

You can make the same case about Jeremy Corbyn and the far-left MPs of the Labour party. They defied the Labour whips countless times. They stuck to their beliefs in the most inhospitable climate until the moment came to take over Labour. They did not rule the country so did not have the chance to inflict the damage the Brexit right caused. But Corbyn’s leadership ensured an ineffective Labour campaign in the 2016 Brexit referendum and gave Boris Johnson a free pass in the 2019 general election.

Stewart can’t tackle the populist revolt because in his strange way he became a part of it. He stood for the leadership of the Conservative party in 2019, and his candidacy provoked a brief mania among young voters desperate for an alternative. As with Nick Clegg and Jeremy Corbyn the spasm of wild popularity did not last long, and the Tory press made damn sure that the liberal Stewart was damned in the eyes of Conservative backbenchers and party members.

Days before his book came out, Stewart offered a revealing insight into his character. He said it was “disgusting” that Starmer removed the whip from Corbyn. (Apparently Corbyn’s inability to accept the conclusions of the inquiry into antisemitism in the Labour party he presided over did not bother Stewart at all.) Like Farage and Johnson, Corbyn and Stewart were English public-school boys who made a virtue of ignoring conventional wisdom. Like them, their careers are over (for the time being at any rate).

Their populist world has failed as surely as the neo-liberal order collapsed in 2008. Labour is trying very old fashioned tactics in its search for a way forward. It has a leader who keeps Labour under control, in as much as that fissiparous party can be controlled. It has a programme to allow the country to start building again, to restore relations with the EU and to tackle inequality. Starmer will expect his MPs to be as unlike Rory Stewart as it is possible to be: boring, unflashy, and disciplined.

Whether such a throwback political party can survive in the 2020s remains to be seen. Rory Stewart and politicians like him will hate it: but it remains the UK’s best shot. Maybe its only shot

If you like my writing, please consider signing up or taking out a free trial for a paying subscription. There are all kinds of benefits AND you allow me to carry on working.

There’s a free trial and subscriptions cost just £1.15 a week.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Writing from London to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.