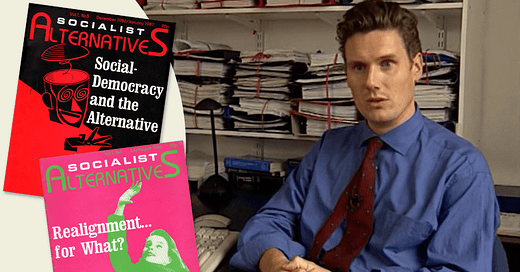

Starmer as a young lawyer at Doughty Street Chambers (Credit/ The Times)

Keir Starmer is not boring. Voters may say he is. His careful language and habitual expression of a faintly startled wombat may confirm their impression. He gives every appearance of being a dull, responsible figure an exhausted Britain is turning to after the spasms of Corbyn, Johnson and Truss.

The UK is in the final scene of the Lord of the Flies. Delinquent children have burned the place down, and Starmer is the leader of a rescue party come to save us from ourselves.

Yet there is nothing remotely tedious about Keir Starmer. He has the potential to be one of the most extraordinary figures in modern British history.

Whether or not he is capable of realising that potential and leading the UK out of its crisis is a question I will attempt to answer later.

For the time being let us look at how unlike contemporary political leaders Starmer is.

In an age when wealthy and privileged men hide their private-school accents and bellow that they are the true tribunes of “the people,” Starmer is from the working class.

But he is from an unfamiliar corner of working-class England that does not fit into national stereotypes. Starmer’s family was not from the industrial cities of the north, Wales, or Scotland, which produced so many Labour politicians. He comes from the small Home Counties town of Oxted in Surrey – a place that can seem so comfortable it is easy to overlook that, like everywhere else, it has class hierarchies of its own.

With a matching novelty, there is no doubt that Starmer is a genuinely selfless man.

Tom Baldwin has written a biography he describes as “authoritative but not authorised”. Starmer cooperated, as did his family and friends. But Starmer did not have copy control, and Baldwin spoke to his enemies too. The result is a powerful book that is as much a history of the hopes and frustrations of the centre-left over the last 30 years as a life of Starmer.

It’s not a hagiography. Baldwin is an activist as well as journalist. He helped run the tragically doomed campaign to keep the UK in the EU after 2016 and worked for Ed Miliband.

He knows about the brutalities of politics and is more than willing to share his knowledge.

Yet running through his narratives are stories of Starmer’s altruism, which the most cynical reader cannot dismiss.

When he was a young lawyer, Starmer repeatedly stopped his paying work to help the victims of injustice free of charge. The most striking example was the McLibel trial of 1997, the longest-running civil case in English history and one of the most notorious.

McDonalds, the vast global corporation, decided to sue two green activists, Helen Steel and David Morris in the ferociously expensive London courts.

Their “crime” was to have produced a six-page leaflet titled, "What's wrong with McDonald's: everything they don't want you to know”.

It discussed the cruel treatment of animals and low wages for workers, and was wholly obscure. Only a few thousand people could have read it at most.

McDonalds thought that two poor campaigners could not begin to afford the costs of the English civil law, and would beg for forgiveness, as so many do when faced with a legal system designed to favour the super-rich.

Their defeat could then be used as PR to counter other accusations of corporate wrongdoing.

Instead of capitulating, Steel and Morris defended themselves in court. McDonald’s looked like what it was: a corporate bully using the biases of the English law to warn others from challenging it.

In the background the young Keir Starmer guided Steel and Morris through the law, so that by the end of the case, it was McDonald’s not the activists who were on trial.

Baldwin writes:

"Maybe it was the kind of case he gravitated towards because it was about helping a pair of outsiders and he still felt like that a bit himself. In interviews at the time, he described them as challenging the system: ‘Even with limited resources, even unable to bring all the evidence to court, you can still win significant victories, through a belief in what you’re saying, a belief in free speech, and the courage to continually put your case forward’.”

When McDonald’s realised their intimidation had backfired, they offered Steel and Morris a settlement on condition they did not say what they thought about McDonald’s to anyone ever again.

Starmer helped them write a letter back saying they would consider the terms, only if McDonald’s ceased telling people what it thought too, and stopped all its advertising. You can’t say fairer than that,

Even now, years on, when he is leader of the Labour party, and you would expect him to be more bruised and wary, Starmer has an engaging willingness to talk to everyone.

Baldwin tells the story of Starmer on a campaign tour

“Some lads started shouting stuff like ‘You’re not getting our vote!’ ‘Labour’s finished here!’ Keir went over to talk to them and they seemed a bit embarrassed because they hadn’t expected that. He then arranged to meet one of them outside a pub the next day,’ he says. ‘I think this guy was astonished when I turned up,’ says Starmer, picking up the story. ‘We had quite a long chat. He was ex-forces, suffering from PTSD and had all kinds of problems in his life.”

It wasn’t a performance for the cameras. There were no cameras.

Starmer has a highly developed personal morality, and hates it when his integrity is questioned.

He was a brilliant left-wing lawyer who was inspired by the human rights movement of the 1990s and went on to be Director of Public Prosecutions.

He only entered Parliament in 2015 when he was in his 50s. Angela Raynor, his deputy, told Baldwin that “Keir is the least political person I know.” He was not associated with any Labour faction. He was more concerned about what was right than what was politic.

When he became leader of the Labour party in 2020 after the disaster of Corbyn’s rule, commentators assumed he would never go further.

Labour had gone down to its worst defeat since 1935. Boris Johnson was triumphant. Starmer would be a transitional figure trying to revive a stricken centre-left. The next Labour prime minister, if there was one, would take power around 2030.

And so it seemed. Here was Keir Starmer who had barely been in Parliament. A moral man but a naïve one. The Left would hate him and the Tories would destroy him.

Like so many other Labour leaders he would fail. (It’s always worth reminding those who think it is easy to beat the Conservatives, just four Labour leaders have come to power by winning a general election in the last hundred years.)

Only Starmer’s friends dissented. They knew a man who was determined and utterly ruthless.

Jamie Burton, a barrister at Starmer’s Doughty Street Chambers, said, “Everyone was telling me he had no chance of victory in a general election. I said to them, ‘Just watch – he’ll win – it’s what happens to this guy.’ On a football pitch, just like when he was a barrister, he’s always in the right place at the right time – goals out of nowhere – he only knows how to win’.”

And so it has proved.

In 2015 he decided to become the Labour candidate for his part of London. The constituency of Holborn and St Pancras is one of the safest Labour seats in the country and the competition was tough.

Starmer wooed party members – although he is still stiff on television, everyone attests that he is very convincing in person – and covered every contingency. Even before he’d formally announced his candidacy, he had become so omnipresent at meetings and events the local paper dubbed him ‘Mr Everywhere’.

It was the same after the anti-West left took over the Labour party. Starmer knew that Corbyn’s leadership could not last.

Unlike many of his colleagues, Starmer did not refuse to serve Corbyn or walk out of the party in disgust at the far left’s antisemitism.

He calculated that party members would only accept a politician who had been alongside Corbyn in the shadow cabinet as Labour’s next leader. Then he went to work to make sure that he would be that politician.

Once again, no trick was missed. A key component of the electoral college in Labour leadership elections are the affiliated trade unions. “MPs and the media hardly ever go to trade union conferences these days,” his adviser Chris Ward said. “But pretty much whenever and wherever one was being held, Keir was there.”

To make Labour electable, Starmer has now abandoned the left he served when Jeremy Corbyn was leader. I will get to the claim by Corbyn’s supporters that he is a traitor when I look at what a Starmer government will do with power.

But be in no doubt they have every reason for loathe him.

After Corbyn refused to issue an unequivocal apology for the anti-Jewish racism in Labour on his watch, Starmer took away the Labour whip. Corbyn, the Labour leader from 2015 to 2019, will not be a Labour candidate in the next general election, I can find no precedent for a former party leader being driven out by his successor.

Meanwhile hardly any of Corybn supporters have been selected as Labour candidates. Thousands have been expelled from the party or resigned.

For a political innocent, Starmer can be bloody ruthless.

One underexamined element of his appeal is that he exemplifies an unfashionable but appealing version of masculine toughness. It is the opposite of the braying chest-thumping masculinity of Trump and Johnson.

He has always been reluctant to talk about himself. Baldwin’s book is the first time he has discussed his hard childhood. Starmer is from a culture where you don’t blab in public about your problems.

An unfashionable culture, as I said, but one that appeals to many, particularly when our dominant ethos of emotional incontinence has not brought a noticeable increase in happiness

Starmer followed the classic escape route for a bright working-class boy: grammar school, university, the professions.

On his way he developed an admirable aversion to bullshit. As Baldwin puts it, he “remains suspicious of the kind of networking conversations that mention this or that university – quite often Oxford or Cambridge – and how someone must know so-and-so because they went there went there too”

As with so many of us, Starmer’s background explains a great deal. He got his left-wing politics from his parents. (They named him “Keir” after Labour’s first leader Keir Hardie, which was a novel choice to make in Surrey in the 1960s to put it mildly.)

His mother Jo, was diagnosed with Still’s disease, a relatively rare condition in which the immune system attacks itself. She endured her suffering with great stoicism.

“Mum was very ill many times as I got older,” Starmer told Baldwin. “She was often told she would never walk again. But then she did walk again, again and again. She would never dwell on her problems. ‘How are you, Mum?’ ‘I’m all right. How are you?’”

He remembers hating trips to the hospital, seeing his mum with “all kinds of tubes in her”, and his parents always trying to get everything back to normal as swiftly as possible. The experience made him “slightly intolerant of people who complain about being ill all the time even if there really isn’t much wrong with them.

“It’s not my best trait, but you don’t need to be the world’s greatest psychiatrist to see why it’s there.”

His mother was nurse, his father was toolmaker and Starmer grew up in some poverty.

His childhood as much as his career as a radical lawyer make me highly suspicious of the left’s claims that he is a sellout.

But his childhood also gave him another quality that those who get in his way should remember. Like many successful people, he had a distant father. I do not want to get involved in cheap psychiatry either but a desire to impress often drives such children on.

Meanwhile Starmer says his mother’s “sheer determination” and her belief in “just getting on with it” have stayed with him. “Faced with a problem,” he says, “I think of her and walk towards it, because compared with what she went through, some of the tougher things just pale into insignificance.”

His remorselessness comes from her. He moved on from being a lawyer to being Director of Public Prosecutions because, for all the money they make, lawyers have no control. They must bow to the decisions of judges, juries and indeed the state legal service. Now that same remorselessness is driving Starmer to power

What will he do with it?

Let me go back to McLibel case.

Helen Steel was not just a victim of McDonald’s. Her tiny green group was infiltrated by undercover police officers. At some meetings there were probably more infiltrators than genuine members. More sinisterly, Helen Steel was in a relationship with a man she knew as John Barker, she had met at the meetings.

He vanished during the trial but she later tracked him down and discovered he was an undercover policeman called John Dines under orders to feign an affection for his targets, and then betray them.

It remains a possibility that the McLibel trial, the longest in British history was set up by police agent provocateurs.

Yet when legislation recently came before Parliament giving the police immunity against prosecution over crimes they commit when they are undercover, Starmer ordered Labour MPs not to vote against it.

He had a reasonable position. If criminals knew undercover cops could not commit crimes, they could devise tests to expose them.

Once that is said, the questions come back. Will a Labour government prevent the abuse of police power? Will Labour initiate a radical attack on the costs of the English law which have made our courts an oppressive instrument for oligarchs and corporations the world over?

Or will it be content with the status quo?

Starmer’s morality, his remorselessness, his principles and his compromises, what have they been for?

I will give what answers I can in the second part of this essay later this week.

Please consider taking out a paying subscription if you can afford to. You will have access to all articles, archives and podcast, and you will allow me to carry on writing!

Best wishes, Nick

Related articles for paying subcribers include

Interview with Tom Baldwin

Can Keir Starmer finish off the radical right?

The Lowdown is available on Apple (see player below) Spotify, Amazon, and all other podcast hosts! This week’s Lowdown podcast is with Tom Baldwin, whose exceptional biography of Keir Starmer is just out. I will do a long piece about our next prime minister and Baldwin’s work later in the week.

Radicalised conservatives cannot save themselves (Or their country)

Brexit supporters celebrating what once seemed a Tory triumph Copyright Alastair Grant/Copyright 2020 The AP

Think too hard about the culture war and you will surely go mad

Taylor Swift and her boyfriend: a threat to all we hold dear? Hello everybody, and a special thanks to everyone who signed up as a free or paying subscriber last week. As I keep pointing out, paying subscribers not only have access to everything on this site, they also allow me to carry on working, so I am truly in your debt!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Writing from London to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.