"Don’t cause trouble!" The only rule of modern censorship

Woke capitalism and the book business

If publishers were honest, they would stop authors breaking their hearts and wasting their time on books their editors would never accept. They would post on their websites the rules of modern publishing that no writer can break. These appear to be

We will not publish an author from one culture or identity who creates characters from another culture or identity

We will not publish misogynist, racist, homophobic or transphobic work

If, by mistake, we publish a book that results in online criticism from the cultural left, however false or self-serving, we will pulp it and abandon the author.

They don’t do it because the law treats publishing as a public service. Like many countries, the UK does not levy sales taxes on books because, as the International Publishers Association puts it, “books are strategic assets that activate the knowledge economy, they facilitate upward social mobility as well as personal growth, and they bring widespread medium and long-term social, cultural and economic benefits.”

The people at the top of cultural bureaucracies are often unable to express themselves in plain language, which is why they become bureaucrats rather than writers in the first place. But I hope you can translate the jargon or at least catch the general drift. Publishing benefits society. Like food and children’s clothes, which are also tax-exempt in the UK, freedom of thought and free debate are necessities, not luxuries to be taxed.

On this reading, publishers are not just cheerful traders, who will take an opportunity to make a quick profit if they see one. They have a higher calling to protect and extend culture.

If publishers admitted they were operating a de facto system of censorship, then governments might wonder why taxpayers should subsidise them when our dilapidated public sector is so desperately short of funds.

The bigger reason no one wants to be explicit, however, is that censorship is random. There are no real rules, just muffled rebukes, and barely articulated taboos. If there were a rulebook, at least writers would know where they stood, and like writers throughout history, would find ways to subvert the censors.

But rules need coherence, and today’s censorship is driven by a desire to conform and fear of denunciation rather than a coherent political programme.

This week the novelist and anti-Trump campaigner Richard North Patterson described the treatment of his latest work. Publishers should have snapped it up. Of his 22 previous novels, 16 had been New York Times bestsellers. Patterson is an American liberal, who spends as much time writing for the Bulwark and other anti-MAGA sites as producing fiction. He took a break from his activism to write his latest novel, “Trial,” about the son of a black voting rights activist the police accuse of murder.

If the book business were a vulgar business, which churned out novels the public wanted to read, he would have faced few problems. But, as he recounted in the Wall Street Journal, publishers rejected a white author because he “chose to write about some of our most vexing racial problems –voter suppression, unequal law-enforcement – through the prism of three major characters, two of them Black.”

Creating African-American characters made him guilty of cultural appropriation. The question he was left asking was “whether empathy and imagination should be allowed to cross the lines of racial identity”. As Patterson said, people are free to dislike his books. But censorship based on the author’s identity was “illiberal, intolerant, ignorant of the ways of creativity, and inimical to the spirit of a pluralist democracy.”

He is now serialising the novel on his Substack, and hopes that a small publishing house will release it in the summer.

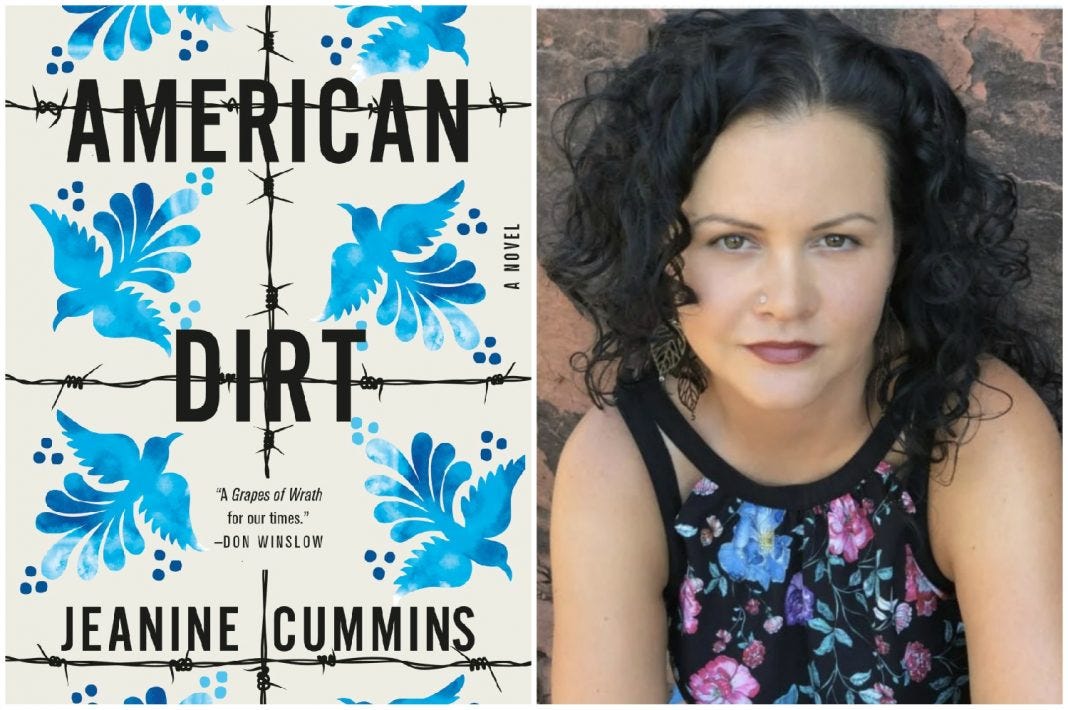

Before him there was Jeanine Cummins, whose American Dirt, told the story of a Mexican bookshop owner fleeing to the US. Macmillan, her publishers, ought to have been delighted. And when the manuscript arrived in 2020, they were.

“I remember telling my boss, ‘I feel like this is finally a book about immigration that people who have no interest in immigration will read’,” an unnamed editor at Macmillan told New York Magazine. Don Winslow called it “a Grapes of Wrath for our times” and Oprah Winfrey chose it for her book club. Sales of more than three million subsequently vindicated their enthusiasm.

But to her enemies Cummins was inauthentic. True, she had a Puerto Rican grandmother, and her father was brought up in a Hispanic culture, but that was not good enough. One accused her of having “the gringo appetite for Mexican pain”, and “a preference for trauma porn that wears a social justice fig leaf”. Despite the sales, and despite Cummins’ ability to connect with readers, Macmillan could not bear the abuse.

Pamela Paul, a former literary editor, described the aftermath in the New York Times

“Looking back now, it’s clear that the American Dirt debacle of January 2020 was a harbinger, the moment when the publishing world lost its confidence and ceded moral authority to the worst impulses of its detractors,” she said.

Ever since, publishers have become wary of “Another American Dirt Situation, which is to say, a book that puts its author and publishing house in the line of fire.”

Books that would once have been published are now passed over, she continued. Sensitivity readers were everywhere, and frightened writers self-censored.

“A creative industry that used to thrive on risk-taking now shies away from it. And it all stemmed from a single writer posting a discursive and furious takedown of American Dirt and its author on a minor blog. Whether out of conviction or cowardice, others quickly jumped on board and a social media rampage ensued, widening into the broader media. In the face of the outcry, the literary world largely folded.”

It’s a reasonable guess that the abuse directed at American Dirt explains the treatment Richard North Patterson received. Meanwhile, on this side of the Atlantic, one of the most shocking episodes in the recent history of British publishing was Picador’s decision to turn on its own author, Kate Clanchy. Her book about refugee children, Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me won the 2020 Orwell Prize. But it took only a handful of Twitter critics to accuse her of being racist, classist and disablist, for Picador to abandon her and drop the book even though her former students defended their teacher.

I could go on. But my point is that there is no solid ground for writers and readers to stand on. The new rule in publishing appears to be that no one can write about a culture or ethnicity they do not belong to. If cultural bureaucrats enforced it, we would have an Apartheid of the imagination, and it is not at all clear that publishers want that.

In 2016, for example, Jonathan Franzen said that he would not about racial conflict because he did not have many black friends. No one congratulated him for “staying in his lane.” On the contrary, they wondered why he didn’t have many black friends.

If supporters of cultural appropriation meant what they said, black authors could not right about whites (and vice versa), men could not write about women (and vice versa) the poor could not write about the rich (and vice versa) and we would end in solipsism where the only legitimate subject for novelists was themselves.

None of this to say that critics do not have every right to damn and mock to high heaven unrealistic and stereotypical writing in the most robust language imaginable. Nor should they be barred from asking why so few working class and minority applicants end up working in the book trade. But the freedom to criticise is not what publishing is offering. It is engaging in pre-publication censorship, the most invidious form of censorship there is, to prevent criticism from the left from ever happening rather than welcoming robust debate once they released a book.

Essential writing is now endangered. Twenty-two publishers turned down an investigation into the scandals at the NHS’s Tavistock gender dysphoria clinic. The author Hannah Barnes worked for the BBC and had conducted an impartial inquiry into the treatment of young and often autistic patients. Publishers praised her work “as an important story that should be told.” But not by them. They could not touch anything, however authoritative, that lobbyists or young members of staff could construe as transphobic.

Or as one editor, who wanted to publish the book but had to take the decision all the way to the chief executive, the boss did not want a book that was “too controversial.”

Nothing on publishers’ websites tells Barnes or any other author what subjects or approaches are “too controversial”. They offer no definitions of racism, classism or, in her case, transphobia. Instead of clear rules, writers are meant to intuitively grasp the restraints on what is acceptable. Eventually, Barnes reached a small publisher that was willing to take a risk.

The monopolistic structure of the books business makes risk-takers hard to find. You don’t need to persuade or intimidate many people to alter the literary culture. Just five companies dominate the market in the UK and the US. Get to them, and you have the industry pretty much sewn up.

If publishers were less high-minded, they might produce a better society. The cheerful trader who just wants to get rich wouldn’t give a damn about what someone said on Twitter. English literature graduates working in an oligopoly care very much. The more so because they are overwhelmingly white and upper-middle-class and must carry the burden of liberal guilt as lepers once carried their bells.

Like so many credentialed people from good universities and comfortable backgrounds, the only rule they truly understand is: “Don’t cause trouble!”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Writing from London to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.