Assisted dying and our competing visions of hell

Why we need the right to die

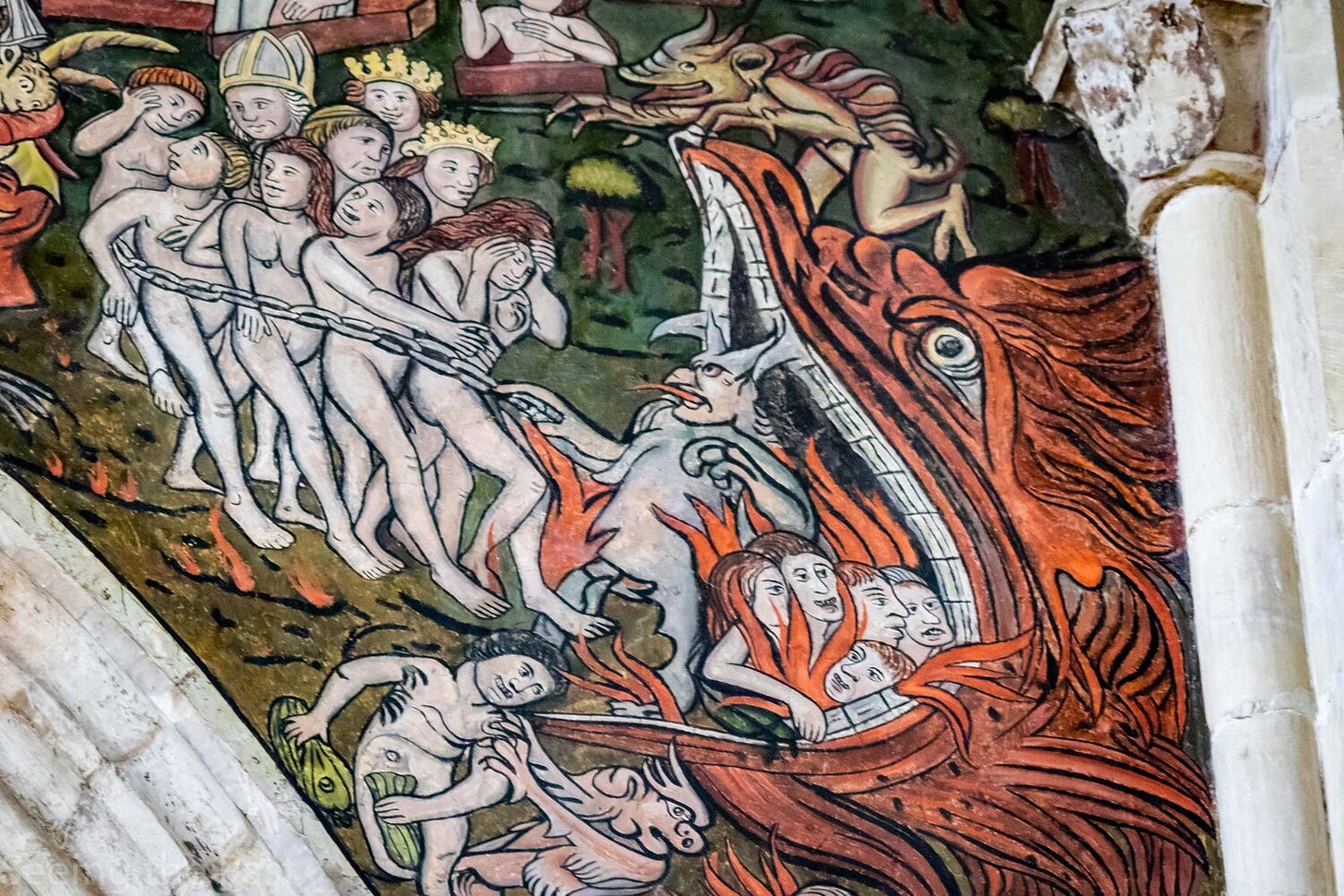

Souls in hell from St Thomas a Becket church Salisbury

On one side of the assisted dying debate is the fear of the hell of unbearable pain. As medicine has extended life without extending healthy life, many of us have seen pain and fear on the faces of grandparents and parents. We don’t want them to suffer or to suffer ourselves.

I saw my father-in-law kept alive for years with drips and nappies and thought that, if a dictatorial regime treated political prisoners like this, we would report it to Human Rights Watch.

“Better an end to horror than horror without end,” goes the German saying. Opinion polls show about two thirds of the public want the right to have help to end their lives.

In the UK, a backbench MP Kim Leadbeater is bringing forward on Friday a modest measure to allow assisted dying or, assisted suicide, if you prefer.

Before doctors or anyone else can help you die, you must be an adult, you must have mental capacity to make the decision to end it all, doctors must say you have six months to live, and you must repeatedly demonstrate that you have a “clear, settled and informed wish” to die which is "free from coercion or pressure.” And just to be sure two independent doctors and a High Court judge must approve the death.

Not surprisingly, Leadbeater says that if her measure becomes law many will complain that it is too restrictive.

Her critics are appalled, however.

To mark the anniversary of my Subsack launch I am offering a 20% discount to new paying subscribers.

This makes an annual subscription just £48 ($60), or £4 ($3.17) per month or only £0.92 ($1.16) per week. In return you have access to everything!

Campaigners for assisted dying expected the main attack to come from the religious, whose fear of pain is outweighed by the fear of hell. All the Abrahamic religions damn suicide. Islam forbids suicide for the same reason as orthodox Judaism and most variants of Christianity. “And do not kill the soul which Allah has forbidden [to be killed] except by [legal] right,” says the Koran. God creates life and it is a sin to take it away.

The result has been cruel and absurd laws from the Middle Ages onwards. As late as 1961 suicide was a crime, and anyone who tried and failed to take their life faced prosecution and imprisonment, as if either would do any good.

Liberals know how to take on church and state. We have been fighting them since the Enlightenment. Assisted dying looked like being a classic liberal fight for the rights of the individual.

But it has turned out to be more complicated than that. To be sure, the bishops of the Church of England, the Chief Rabbi, and virtually every other religious figure has come out against the measure. And fear of hell or fear of God motivates them.

But most of the opposition is moved by dystopian views of British society and its citizens rather than liberal conviction. If it is a fear of hell, it is a fear of Jean-Paul Satre’s hell of other people.

So when Lord Falconer, a great campaigner for dignity in death, said that the opposition of Justice Secretary Shabana Mahmood to assisted dying was motivated by her religion, he didn’t really get it right.

Mahmood echoed, instead, a deep suspicion of the British state that is everywhere today. That Mahmood, a Labour politician, who in theory believes in the power of state to bring change is so mistrustful, shows how profoundly the decline of post-Brexit UK has depressed morale.

In a country where nothing works, we can’t die in peace,

“Sadly, recent scandals – such as Hillsborough, infected blood and the Post Office Horizon – have reminded us that the state and those acting on its behalf are not always benign,” she said. “I have always held the view that, for this reason, the state should serve a clear role. It should protect and preserve life, not take it away. The state should never offer death as a service.”

Note the role reversal. Now it is the supporters of assisted dying who are on the side of malign state power.

And what applies to a malign state applies to your malign family. All campaigners against reform raise the dystopian spectacle of greedy children pushing a rich parent into an early grave.

I take these concerns seriously. But I wonder why there is so little evidence from countries that have legalised assisted dying to back them up. I hope the measure passes because at the end of the 2010s, I saw a friend escape from terrible illness.

I hope my account from 2018 of Nyta Mann’s life and death explains why change is needed.

Nyta Mann was never famous. Few beyon her family and friends will register her passing. I am one of the few who remember her spiky, arch conversations and regret that I will never hear her again. Her death showed how hopeless I and perhaps modern society are at acknowledging suffering

.

We can acknowledge victimhood. We manufacture victims like the Victorians manufactured heroes. Victims are comforting in their way because we can plan and, on occasion, achieve the removal of the forces that oppress them. The inequalities of wealth, power and gender are as nothing, however, when set against the greatest inequality of all. No reform or revolution can heal the divide between the well and the sick, which we will all stagger across one day.

In 2016, Nyta asked me to visit her. She was no longer in a hutch thrown up in the East End to cash in on London’s delirious property inflation, but in a fantastically expensive art deco apartment overlooking Hyde Park. She had cashed in everything so she could live like a princess for a few years. I soon learned why. She had multiple sclerosis in its most relentless form. Her body was going and perhaps her mind would follow.

Nyta made me promise two things. I was to join her for a farewell dinner in Switzerland the night before she went to the Dignitas clinic. In the interim, I was not even to try to persuade her to change her mind. I broke the second promise at once.

While he was dying from oesophageal cancer, Christopher Hitchens wrote that he no longer cited Nietzsche’s slogan “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger” with the same conviction. As he was learning, patients in the rich world suffer conditions that leave them weaker and in more pain for longer than any previous generation endured.

Only the (temporarily) healthy, on the right side of the greatest inequality, can still dream the Nietzschean fantasy. We want stories of redemption. We talk of “struggles” against cancer and “fights” against diseases, as if mere fortitude can overthrow the suffering of the human condition. I shouldn’t need to add that our myths are self-serving. They allow us to imagine that we, at least, will have the guts and determination to recover when sickness strikes. I should recognise these comforting lies for what they are. I am allergic to the uses of what Tony Judt once called in another context “the cheating language of equality”. When a British government, which is closing services for mentally handicapped children, announces in its most politically correct voice that it is wrong to say “mentally handicapped children” rather than “children with a learning disability”, I see a modern version of Victorian cruelty deploying euphemism to cover cynicism.

Nevertheless, for all I knew, or thought I knew, I disobeyed Nyta’s instruction and argued with her. It is a human reaction, I think. If you see a stranger about to jump from the ledge, you try to talk them down. The desire to persuade them to choose life would only become more urgent if you discovered they were a dear friend. Nyta dismissed me with contempt. It was her decision. People who still inhabited the world of the well did not have the knowledge of suffering to question it.

The invitation to her farewell dinner came in May. I am not going to lie. I was relieved – immensely relieved – to discover that it fell in the middle of a prebooked holiday I could not cancel. I would not have known what to say or do. Death cannot be sanitised. Dignitas is a “clinic” that kills people. To kill a woman in a wheelchair, it needs collaborators to get the “patient” to the airport, the hotel and finally the clinic itself. Would I have collaborated? That was a question I didn’t want answered. Instead I phoned her.

“I’m calling to say goodbye.”

“Goodbye, then.”

“Oh Nyta.”

“Don’t ‘oh Nyta’ me. It’s what I want.”

One lesson from Nyta’s life needs to be learned now. Parliament will not be able to withstand the pressure from the public to make assisted suicide legal for long. If you plan your death, you must get the consent of all the people you will need to help you, as well as being absolutely sure that death is your desire. Nyta was adamant from the beginning to the end. She never complained or self-dramatised. Her Twitter feed made no mention of her coming suicide. Her last tweets were political, not personal. They merely recorded that she was leaving the Labour party that she had served and reported on for decades because she could not stomach Corbyn’s endorsement of Brexit and his treatment of the Jews. Her stoicism makes her sound the “strong woman” all modern women are meant to be. But the language of “empowerment” cheats too.

Despite the advances of feminism, Nyta’s strength of mind didn’t help her in a world where spiky women are still meant to suppress their intellects. She was a political correspondent for the New Statesman in the 1990s. It broke her heart when it fired her in one of its periodic purges. (The vicious office politics of small magazines are always in inverse proportion to their circulation.) She moved to BBC Radio’s chatty news and sport station 5 Live, but couldn’t play along with its mandatory chirpiness and resigned. Talk of strength is in any case a lie when applied to the chronically sick. Suffering does not make you better.

So there lies Nyta Mann (1967-2018). I would raise a glass to you, but I’ve stopped drinking. I’d say a prayer for you, but I no more believed in primitive tales of god and gods than you did. The best I can do is say you died the way you lived: on your own terms. And how many of us will be able to claim that epitaph when our time comes?

Because more of us should be able to die on our own terms, I hope Kim Leadbeater’s bill passes.

I am offering a special anniversary offer this week.

The 20 percent discount on subscriptions makes an annual subscription just £48 ($60), or £4 ($3.17) per month or only £0.92 ($1.16) per week. Frankly, I can’t think of anything beyond a couple of carrots you can buy for £0.92 these days.

Paying subscribers have unlimited access to all my articles, archives and to the Lowdown podcasts. They are also able to join the civilised debates in the comments section.

I need to add that your subscriptions allow me to make a living and to work without pressure from advertisers, sponsors, and media magnates, and are hugely appreciated.